When Texas went to the United States Supreme Court last month complaining about the election processes in four other states, the case was dismissed on the issue of standing. The Court correctly replied Texas had no right to complain about how the Electoral College votes were determined in other states but could only control selection of its own presidential electors.

But what if Texas had been part of an interstate compact that required it to choose electors based on which candidate won the highest number of votes in the entire nation? That is what the National Popular Vote Compact does: States that join, once enough agree, ignore the will of their own voters. They will certify electors pledged to the candidate with the most votes overall, even if that person failed to win in that state. Suddenly they have a larger stake in how those other states run elections.

Might Texas then have had valid reason to poke into the election process of Pennsylvania or Wisconsin and challenge its rules? Challenge a quirky rule about eligibility? Review challenged ballots on its own? Virginia might be able to do the same (or be challenged), because the 2021 General Assembly is being asked to join the National Popular Vote Compact. Legislation failed in 2020 but may pass now.

Here is another undiscussed implication of the National Popular Vote approach, illustrated by what we just went through. Suddenly instead of the few recounts we saw after November 3, a nationwide recount is possible. Could voters in one state challenge the recount process in another state? There are many variations in how recounts work – could Virginia send observers to a California recount, or vice versa?

States that do or do not use a universal mail ballot system might file cross claims against each other, arguing which should be the standard.

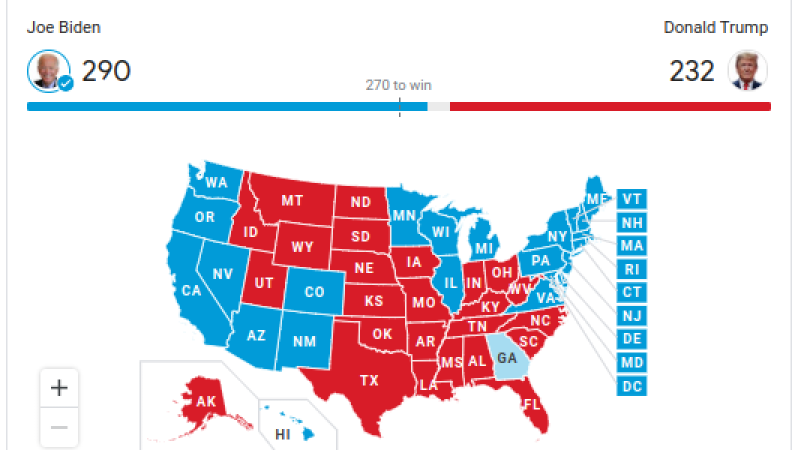

The last two months increased public awareness of our complex path to choosing a U.S. President. They probably added to the confusion over how a candidate can trail in the popular total vote and still win. Perhaps public disapproval of the Electoral College has grown, as feared. More Americans may now want a single national election, not the 51 separate smaller contests we have now.

But the value of our indirect Electoral College process, designed to diminish the dangers of pure democracy and to protect the political importance of individual states, was proven once again. Last year also demonstrated that if enough Americans still want to change to a straight-up national election, the half-baked approach of the National Popular Vote Compact is the wrong way to get there.

The bills to include Virginia in the compact are back in front of the General Assembly that starts tomorrow. House Bill 1933 is sponsored by Delegate Mark Levine of Alexandria and Senate Bill 1101 is sponsored by Senator Adam Ebbin from the same city.

The process they envision is neither a direct national election nor the federalist approach but a weakened hybrid that won’t survive. It comes without any of the rules, guidelines, and protections in a truly nationalized election. Which means we are opening the doors to the legal horrors of the 2020 disputes but with no roadmap or precedent on how to get to the resolution.

Last year, Levine’s House version passed that body on a party-line vote but ran into a wall in the Senate Privileges and Elections Committee. This year’s Senate bill is loaded with co-sponsors, House and Senate, including Senator Majority Leader Richard Saslaw and Senate Finance Chairwoman Janet Howell.

The organization behind the coordinated National Popular Vote campaign has now developed a special tracking page for each state, including Virginia. In 2020 the popular vote and Electoral College result did align, which should reduce the pressure for passage. But the 2016 misalignment has not been forgotten and the massive Democratic majorities available in New York and California are too attractive for Democrats to ignore. The rest of America is swamped by them.

All of the other recent changes to election rules in various states pale in comparison to the impact of this idea, should it be implemented and survive legal challenge. It is simply an end-around on the traditional Constitutional amendment process, which proponents know would be much harder to sell.

At this point, there is no official national vote total. Nobody tallies it and certifies it. Do we take the media’s word for it? Would states, instead of sending a list of electors, send their certified vote numbers to Congress for it to conduct a tally? Would not disputed elections be just as ugly, if not uglier, than through the current Electoral College process?

If there is to be a direct national election of the President, we should make the change by amendment and then address all the new wrinkles it creates. It will have to be a nationally-managed election process with a uniform set of rules and integrity protections. The National Popular Vote structure provides none of that and will create even greater voter distrust.

This is a bad idea whose time has passed, and the 2020 result should lower the heat, not raise it. Senator Creigh Deeds, chairman of the Senate committee that snuffed this last year, said he was reluctant to change Virginia’s process right before the election. Now the next election is more than three years away, and a vote this month might be seen as acting both in haste and in retribution.

This was poorly thought out before. Now it is clear there are even more hidden implications. The National Popular Vote Compact needs to be rejected.